Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989)

Star Trek V marks Shatner’s debut as a feature film director, with his prior directorial experience, like Leonard Nimoy, coming from stage productions and TV episodes. Due to the “favored-nations” contract that stipulated that he and Nimoy get equal benefits, Paramount had little choice. Nimoy directed two feature films, so Shatner received the same opportunity.

After the successes of Star Trek II-IV, producer Harve Bennett moved on from the “Star Trek” series, signing a three-year deal with Paramount to develop projects he wanted to make. Bennett was feeling unappreciated after butting heads with Leonard Nimoy, getting undermined by Gene Roddenberry, and didn’t want to relive it with Shatner. Shatner begged Bennett to reconsider and told him he could have the absolute final say. Bennett accepted.

Shatner pursued Eric Van Lustbader, author of a series of bestselling ninja novels, to write the script based on a story he had in mind. The studio passed on Lustbader due to his million-dollar asking price and desire to retain rights to the story. Shatner wrote a fourteen-page story outline titled, “Star Trek: An Act of Love”, where a rogue Vulcan prophet named Zar hijacks the Enterprise, taking its crew to a distant planet where he feels God resides. After getting through the Great Barrier to go “where no one has gone before,” they meet “God” only to discover he is Devil in disguise and they’re literally in Hell.

The inspiration for the story came from Shatner’s observing televangelists who’ve claimed to talk to God. He wondered why God chose them to talk to and why he needed them, given that God is almighty. Some religious leaders did despicable things claiming that God told them to, which made Shatner question whether the Devil could pose as God to fool them into committing evil. Bennett wasn’t fond of the idea, thinking it similar to Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Paramount approved it, though, so long as Shatner peppered the dark plot with comedy, a la Star Trek IV.

Shatner stated that his shift toward the spiritual side of things was due to the aging characters, who naturally would be at a place where they began to think about death and the possibility of an afterlife. The moral lesson was that God was not a being you meet on a planet in space, but lives inside each one of us. He felt this would be a meaningful adventure for those who’ve been with the characters and seen them grow into old age.

Shatner and Bennett smoothed out story wrinkles, maintaining intrigue by reducing overexplaining Sybok’s rationale for hijacking the Enterprise to search for God. Sybok should see himself as a hero but a madman to Kirk. As they honed the story, Bennett felt they might pull it off. So long as the journey is fun and exhilarating, audiences might overlook any disappointing elements in the climax. Paramount and Bennett developed cold feet regarding whether God or Satan should exist in the ending. They felt hat many viewers might find the depiction offensive to their own beliefs. Series creator and executive consultant Gene Roddenberry agreed, feeling that “Star Trek” should avoid literal religious themes.

Ironically, Roddenberry went down a strikingly similar road before with “The God Thing”, a rejected idea for the first film in which the Enterprise crew encounters God, revealed to be an ultrapowerful alien. Yet now he argued that Shatner’s idea resorted to fantasy, not science fiction. Roddenberry consulted sci-fi authors Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, who agreed that Shatner’s ideas were childish and possibly offensive. The only way to retain sci-fi integrity is for “God” to be revealed as a super-alien. Having the crew meet the real “God” or “Devil” eroded the established scientific foundation of “Star Trek”. He felt the script had more “Star Wars” influences than “Star Trek”, especially Sybok’s effortless Jedi-like manner of manipulating the Enterprise crew to do his bidding.

Roddenberry despised using the secondary players as comic relief to set up obvious jokes while the others played heroes. He also hated how the characters so easily turned to side with Sybok without question or even any skepticism or disbelief at all in the main reason for the adventure ahead. It was revealed years later by someone who worked with Roddenberry that his opposition likely stemmed from feeling hurt by Paramount green-lighting Shatner’s story when his own version of that same story had been dismissed.

“God” became a super-alien as a compromise to all sides, but they still needed someone to write the script. Both Bennett and Shatner courted Nicholas Meyer but he had his hands full directing 1988’s The Deceivers. After pouring through a hundred unproduced scripts, Bennett came across an incisive, clever, and very witty one for what would later become the 1990 film, Flashback, from David Loughery, who Paramount had under contract. He had one screenplay credit, 1984’s Dreamscape, which they enjoyed. They found Loughery to be enthusiastic, personable, and very funny – the perfect fit for what they wanted to achieve. Secretly, Loughery had been reluctant but felt he wasn’t in a position to say no. He had familiarity with “Star Trek” but wasn’t particularly a fan.

Plans were to release the film for Christmas of 1988. A prolonged Writers’ Guild of America strike tightened the preproduction and shooting schedule. Shatner used the downtime to write the first in his series of “TekWar” novels. Meanwhile, Paramount had yet to secure contracts for the cast, leaving Nimoy free to direct Touchstone’s The Good Mother, pushing the release of Star Trek V into the summer of 1989. Another scare occurred when DeForest Kelley suffered a collapsed colon, requiring major surgery, but he recovered in time for the scheduled shoot. During this period, Shatner decided he’d like to soften the nature of Zar, changing his name to Sybok to conform with traditional Vulcan naming conventions. Shatner began to have second thoughts about him coming across as an intense and evil terrorist or a second-rate version of Khan.

When the strike ended, Loughery revised the script with these new ideas while Shatner flew to the Himalayas for two weeks to fulfill his obligation to participate in an environmental-minded mini-series for TBS called “Voice of the Planet.” Upon return, Shatner discovered that Bennett and Loughery had made some major script changes without his knowledge or approval. They thought Shatner was going to love their ideas, but instead, he felt betrayed. They had written out the search for God altogether. Instead, the quest involved finding a mythical land similar to Shangri-La from “Lost Horizon”, called “Sha Ka Ree”, named in honor of Sean Connery, who left the Sybok role to do another Paramount feature, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Shatner was livid, immediately fighting to restore his original vision, insisting they’d drifted too far. “God” was placed back in the script, though they retained the name of Sha Ka Ree as the place Sybok is seeking. Next, they worked on motivations for the characters for not committing mutiny against Sybok, especially Spock, who was immune to emotional manipulation. Sybok became Spock’s half-brother. Nimoy vehemently protested, stating that, relative or not, Spock would never betray Captain Kirk. DeForest Kelley asserted that Bones wouldn’t either, prompting another major script revision.

Worse news: studio bean counters estimated script elements would greatly exceed their allotted budget and they’d need to scale back. No sweeping panoramas, no Lawrence of Arabia-esque cavalry of soldiers on horseback riding across the desert, no fire rivers, no gargoyles, no angels, no demons flinging thunderbolts. Shatner replaced gargoyles with an idea to have several stony goliaths breaking free from the nearby mountains, but Paramount would only fund one Rockman. Eventually, that too was cut for playing unconvincingly. Shatner soon discovered that the old adage was true: the key to failure is trying to please everyone.

The final plot: the first impromptu mission of the new Enterprise requires them to travel through the Neutral Zone to the nearly desolate planet of Nimbus III, aka the “Planet of Galactic Peace”, where a messianic Vulcan known as Sybok has placed several high-ranking ambassadors as hostages. He hijacks the Enterprise for an odyssey through the Great Barrier, a place that no other ship has successfully breached, to find the fabled Sha Ka Ree, from life is said to have sprung forth. Sybok seeks to find the Higher Being who has beckoned him to spread his word. Is Sybok a madman or a visionary anointed with divine inspiration?

Due to the themes and plot elements, the film had the subtitle, The Final Frontier, which some interpreted as this being the final film for the original crew. Paramount fueled speculation by stating that there were no plans for any future Treks going into Star Trek V and that the expense and busy schedules of Shatner and Nimoy made it unlikely. In reality. Paramount wanted to see how Shatner’s film performed before letting him direct another. When news leaked that the plot involved the Enterprise crew meeting God, rumors spread that the crew dies at the end.

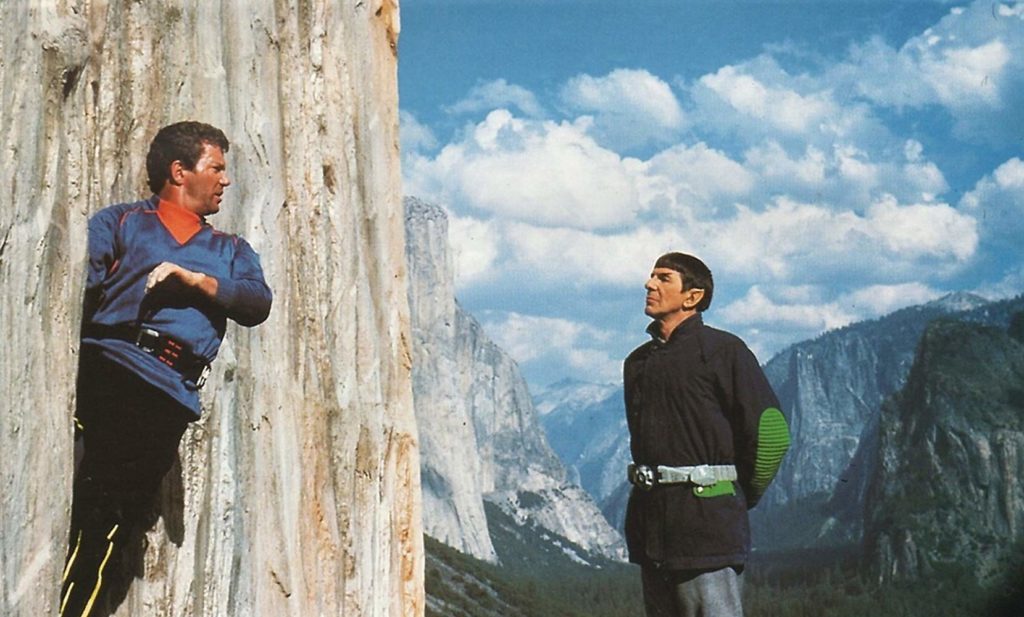

The shoot took place in California locations like Yosemite National Park, the Mojave Desert, the desiccated bed of Owens Lake, and the Trona Pinnacles for the finale. Budgetary restrictions forced additional location shooting into soundstages at Paramount Studios.

Shatner departs from Gene Roddenberry’s vision of “Star Trek” through a more realistic and less utopian vision of space exploration, as we witness attempts at galactic peace falling apart due to malaise and squabbling. Nimbus III scenes come across like Mad Max, sans the high-octane action sequences. He envisioned a Western, using primitive weaponry and horses (Shatner’s passion; originally written as unicorns). The subtitle of “The Final Frontier” evoked the frontier-based Westerns, and nodded to the afterlife.

Laurence Luckinbill takes on the Sybok role, discovered by Shatner while channel surfing, portraying LBJ in his one-man show on PBS called “Lyndon”. Shatner called Luckinbill about the part and he accepted immediately. Coincidentally, Luckinbill is attached to “Star Trek” royalty as the husband of Lucie Arnaz, daughter of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, whose Desilu Productions developed “Star Trek” into a TV series. According to Luckinbill, Nimoy was initially standoffish with him. He speculated it was sour grapes because of a rumor that Nimoy wanted to play Spock and Sybok in a dual role, but couldn’t because Sybok was his half-brother and not his twin.

Catherine Hicks, who portrayed Dr. Gillian Taylor in Star Trek IV, was asked to return for a small appearance, rumored to be a scene where she marries Kirk. However, she declined the role because she didn’t want to only do a cameo.

Shatner felt the eighteen-week postproduction schedule was unbearably restrictive. Though the budget was a series-high $32 million, much of it went to securing the returning actors. Shatner and Nimoy commanded $6 million each, while DeForest Kelley and George Takei required considerable pay increases to return. Harve Bennett suggested they film V and VI back-to-back, but Paramount deemed this as financially risky, opting to wait and see how V fared.

For visual effects, Industrial Light and Magic were expensive and busy with other projects. They shopped around to other effects houses, auditioning them by having them produce an image of God. The honors fell to Bran Ferren’s company, Associates & Ferren, whose credits included Altered States and Little Shop of Horrors. Despite having the highest budget of any Star Trek film to that point, money for visual effects was tight, as was the schedule, requiring Associates & Ferren to reuse models from prior films and place them on rear-projected backgrounds rather than bluescreening, resulting in muddy, low-tech visuals. Some shots were repurposed from prior films. Sets had to be scaled down, including rebuilding the Enterprise bridge at a smaller scale to save cost, while other sets were borrowed from “Star Trek: The Next Generation”.

Shatner’s desired cut ran over two hours. Paramount wanted it cut down to 105 minutes to squeeze in extra theatrical showings. Shatner felt any further cuts would hurt his picture. At this point, Bennett took control, winnowing Shatner’s cut to Paramount’s desired length. This rough cut without music or completed effects played for test screenings did not meet well, eliciting snickers at inappropriate times, starting with the visage of a portly James Kirk scaling El Capitan free-hand. The special effects were laughable, with starships looking like cardboard cutouts flying around. Applause was scarce at the end, creating negative buzz surrounding the picture.

Paramount employed damage control to curtail these rumors, claiming that initial test audiences saw an incomplete workprint. Bennett cut five additional minutes from the ending and added an expository sequence to make Kirk’s rescue less confusing, and it played to test audiences with better success. Despite negative press, Star Trek V debuted atop at the U.S. box office with $17 million, the largest opening for a Star Trek film to date. However, it fell out of the top ten within three weeks, earning only $52 million, the series’ worst-performing until Star Trek Nemesis.

Star Trek V faced brutal competition in the summer of 1989, including Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Ghostbusters II, Honey I Shrunk the Kids, and Batman. This was also the first Star Trek film released during the run of “Star Trek: The Next Generation”, which sated fans’ hunger for anything “Star Trek.” Harve Bennett likened it to Thanksgiving; it’s not being a big deal if you dine on turkey every day.

Shatner starts poorly, as an obvious stunt double scales the stony face of Yosemite’s El Capitan. Kirk is not in anywhere near the shape to climb such a daunting face, but, perhaps due to his ego, Shatner thinks otherwise. The scene gets sillier, as Spock appears in physics-defying jet boots, which he uses to save the falling captain from certain death, even when upside down. The film outdoes itself by venturing into the realm of schmaltz. A campfire scene pokes fun at Spock’s logical stoicism, as McCoy and Kirk sing “Row Your Boat”.

It doesn’t end there. The film is a compendium of the series’ most embarrassing character scenes, from Scotty not being able to walk around the Enterprise without conking his head, to Sulu “wings it” trying to fly a shuttle, and Uhura doing a sultry naked fan dance while singing for a group of ogling barbarians (Nichols fumed that her singing was overdubbed by the band Hiroshima). The cast found relief that working under Shatner’s direction was enjoyable and productive given they despised his primadonna demands as an actor. They found him thoughtful, patient, and encouraging. Not once did he blame his talent for its shortcomings, citing his inexperience and lack of funds as the main obstacles.

Widely regarded as the series’ worst, Star Trek V was Shatner’s chance to join Nimoy in crafting a Star Trek story and directing. There’s a small contingent of loyalists that feel its tackling of thought-provoking moral questions honors the spirit of the TV show. Detractors take the flip side, feeling like it should have been relegated to an episode of “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” keeping the movies as the platform for stories with a broader cinematic appeal. The search for God is worthy of a major Star Trek event and could make a thought-provoking movie. Unfortunately, Shatner made rookie directorial mistakes and the studio made worse financial ones.

Shatner goes against the grain by showcasing the characters we’ve followed for decades in a new light. He felt that the crew’s conversations should be as longtime comrades, forgoing Starfleet formalities. While some informality is in keeping with the lighter tone brought forth from Star Trek IV, Shatner fumbles his characterizations. Shatner plays his part less like Kirk and more like Shatner, a loveable goof, while other characters are shallow parodies of themselves. It’s too late in the series to paint them as anything other than that we have already come to know. When we see a flirtatious relationship between Uhura and Scotty, we can only recoil from the absurdity.

Even if the ending plays confusing and anticlimactic, there’s still ample suspense leading to the approach to Sha Ka Ree. The best element remains a returning Jerry Goldsmith as the composer; even if it emulates work he did for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, it still generates a captivating sense of adventure and mystique. If something needs trimming, it’s a needless subplot involving a bored Klingon captain going after the Enterprise in a Bird-of-Prey to set up more stakes. The light-show finale raises more questions than answers, leaving viewers confounded and dissatisfied.

The first film directed by Nimoy, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, barely even had Spock in it. Shatner’s attempt comes off like a vanity piece. It never quite gels, despite decent moments and interesting philosophical themes. Shatner’s faster and looser Star Trek isn’t Roddenberry’s, and many fans reject this flawed entry. Like the Enterprise-A, it’s clunky and not ready for a real adventure.

Star Trek IV had received four Oscar nominations. The only nominations Star Trek V received were Golden Raspberries (the Razzies) with Shatner winning for Worst Director and Worst Actor, and the film for Worst Picture. Nominations also went to DeForest Kelley for Worst Supporting Actor and David Loughery for Worst Screenplay.

After the acclaimed release of the Director’s Edition DVD for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, which featured a tighter re-edit and substantially improved effects, Shatner asked Paramount for something similar with Star Trek V, but they declined. Although this film is considered canon, Star Trek VI ignored Star Trek V altogether, as did practically all “Star Trek” novels, comics, and TV shows that followed. Watch it or don’t, it doesn’t matter. Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily, Star Trek V is “but a dream.”

Qwipster’s rating: C-

MPAA Rated: PG for some language and violence

Running Time: 107 min.

Cast: William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, DeForest Kelley, Laurence Luckinbill, James Doohan, George Takei, Walter Koenig, Nichelle Nichols, Todd Bryant, Charles Cooper, David Warner, Cynthia Gouw, Spice Williams, George Murdock

Director: William Shatner

Screenplay: David Loughery