Fletch (1985)

Fletch is based on a 1974 novel from Harvard-educated author Gregory McDonald, who had just left his job working as a journalist for”The Boston Globe” to write his book based somewhat on his and his fellow reporters’ experiences. The novel would be a critical and commercial hit, earning its author the Edgar Allan Poe award for “Best First Novel” from the Mystery Writers of America. At the time of its publication, the novel had already been optioned to be made into a feature by actor-comedian Alan King and actor-filmmaker Rupert Hitzig (aka, King-Hitzig Productions) for Columbia Pictures, with author McDonald himself set to script. They cycled through a who’s who of actors to attach, from Burt Reynolds to Charles Grodin, but nothing was sticking.

It had been originally slated to be released in 1975, but persistent delays pushed it into 1976. As there were no studios gung-ho on moving forward, the production would get scrapped altogether when the film rights were sold to a Paris-based company, Fred-Roy Productions, headed by Claude Berda and Jonathan Burrows. Interesting, during this period, Chevy Chase, a former high school classmate of young producer Burrows, was made an offer, but his manager had declined it on his behalf without consulting him. Richard Dreyfuss and George Segal were also pursued but they declined. Burrows became so desperate to get the project sold that he even submitted multiples times, with different titles and binders, but was rejected every time.

However, not much would come of it, leaving the project in limbo until 1980, when British record label Charisma Records vowed to put up $3.5 million to make the film. Charisma Records wanted to put Mick Jagger as the star and the singer seemed genuinely interested. However, McDonald, who had rights in the contract to decline casting choices, nixed it, claiming that Jagger was too far from the all-American type needed for the role of Fletch. Their backup choice of David Bowie was not asked, figuring he would be declined for the same reason. Movie-making was too expensive for the record label and they soon lost interest in making films altogether, shopping around their film rights before their label would get bought by Virgin Records in 1983.

Producer Peter Douglas, who had been interested in seeing the film get made since reading the original novel almost ten years prior, bought out the rights for Fletch with an eye to cast his half-brother, actor Michael Douglas, into the lead role with Treat Williams as a backup choice, but production would still get delayed further, with both Douglas and Williams getting involved in Romancing the Stone and Prince of the City, respectively. Douglas soon connected with William Morris agent Stan Kamen, who would put together a viable package of talent that included director Michael Ritchie, Chevy Chase, and most of the other supporting cast. After shopping the project around, Univeral Pictures bought it, putting Fletch quickly into production in 1983.

However, the studio heads at Universal did not like one thing: McDonald’s original script based on his novel. They were not interested in proceeding as it was, specifically because of the drug-dealing aspects of the undercover case Fletch was working on, which they felt the film market was already saturated with similar stories. They also wanted to change the setting from Santa Monica to Miami to give the setting much more pizzazz. Co-producer Alan Greisman brought out screenwriter Jerry Belson to concoct a new screenplay not based on any of McDonald’s “Fletch” novels that had a film noir vibe, where the beautiful wife of a Latin American dictator would lure in Fletch to help her in part of a murder plot.

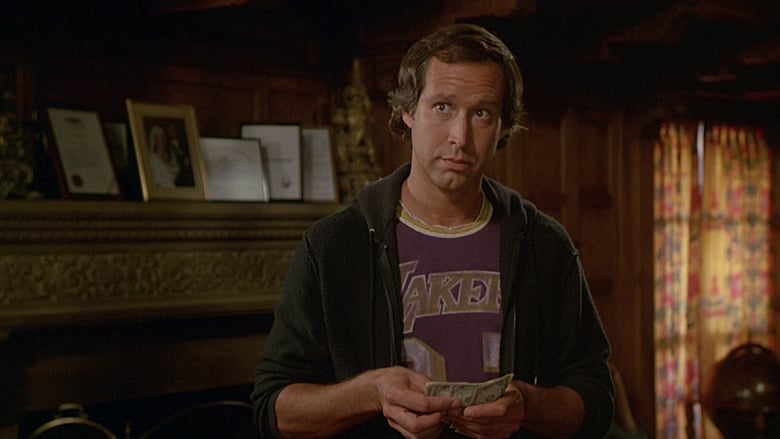

However, Belson’s script was deemed too dark and disturbing by the same execs, so they set about looking to stay with the original concept but with a new script. Andrew Bergman was brought in, not only due to his successful comedy screenwriting experience but also because he was himself an author of a couple of detective novels. Bergman had never adapted someone else’s work before but set about rescripting from the original novel but with the already cast Chevy Chase in mind. Bergman opened up the scope of the book to get Fletch out and about more often instead of having phone conversations and reduced his womanizing and bad behavior with his ex-wives that got in the way of our liking of the character. he gave him more personality, such as being a fan of the Los Angeles Lakers and combining the drug dealer story with the hired hit plot.

Shooting beginning in 1984 primarily in and around the Los Angeles area. Chase was already into his 40s, which was quite a bit older than the young ladies man McDonald portrayed in the novels, but after so many starts and stops, this might be the best they could hope for and still get made. McDonald gave Chase his blessing in a telegram. McDonald felt Chase exhibit the right amount of mischievousness to play the role effectively even if he wasn’t quite the ladies man he envisioned the character to be from the novels.

Chevy Chase plays a Los Angeles Times investigative reporter named Irwin M. Fletcher (he prefers to be called by his nickname, “Fletch”) under the pseudonym of Jane Doe. While working undercover trying to uncover the secret to a major beachside drug ring, Fletch is approached by a wealthy businessman named Alan Stanwyk (Tim Matheson) who thinks he is a transient and makes him an offer of $50,000 to kill him. The story is that he has bone cancer and doesn’t want to be around to enjoy the most painful aspects of the disease and wants his wife to get the insurance on it by getting killed. Sensing another scoop, Fletch agrees and soon learns that the two stories he is covering are almost one and the same.

This role is probably Chevy’s best showcase of his often squandered talents, in which he has to undergo several different disguises in his efforts to get to the bottom of things. His many personas and looks are good for some amusing character comedy, as Fletch adopts a variety of famous names for his characters, including Ted Nugent, Harry S. Truman, G. Gordon Liddy, Don Corleone — even Babar the Elephant gets a reference. Chevy Chase claims Fletch to be his favorite film due to the irony that donning over a dozen disguises allows him to be more of himself, but mostly because he is glib and cheeky as the actor is known to be in real life. He was given free rein to adlib many of his lines in the film scripted by Andrew Bregman, and those names given on the spot were among those he came up within the moment.

Director Michael Ritchie knew that the draw to the film would be as a Chevy Chase starring vehicle first and foremost, so he encouraged Chase to do things the way he wanted, so long as he didn’t deviate from the main plot, or get too sidetracked riffing to not move the story forward when it needed to. They would do each scene according to script and then do additional takes letting Chase riff his dialogue the way he wanted, so long as his improvisation didn’t interfere with the general flow of the dialogue from the other actors, who were allowed to be loose with their dialogue so long as they didn’t deviate from the intent or interfere with Chevy’s shtick.

Indeed, the plot is not particularly interesting taken on its own; most of the fun comes from seeing how Fletch gets in and out of sticky situations, with Chevy Chase’s ad-libs perfectly in sync with how Fletch would have to continue to pile on the put-ons in order to gain information without being outed as fraudulent. The absurdity in witnessing others confused but not quite catching on is what makes it fun, as they aren’t in on the joke that Fletch and the rest of us are. One scene has Fletch breaking into a home guarded by a local rube with a shotgun to whom Fletch asserts while standing in the bedroom, that he is with the Mattress Police and he is investigating why there are no tags on the mattresses.

The film is entertaining and humorous, although the underlying murder plot is not really the main focus, it is what ties all of the comedy together. However, it does spark some moments of interest and surprising gravity, leading Fletch to feel weighty despite its clowning, much in the same way that Beverly Hills Cop had done for Eddie Murphy the year prior. The tone and setting as a vehicle for a comedic actor isn’t the only connection one could draw between Beverly Hills Cop and Fletch; both films feature very memorable earworm-worthy scores from synth composer Harold Faltermeyer as one of the main highlights of the experience, despite coming in late to the project to replace the original composer, Tom Scott.

Also like Beverly Hills Cop, in addition to Faltermeyer’s score, Fletch has on its soundtrack a few songs by popular artists, from the opening and closing credits song by Stephanie Mills called “Bit by Bit” (referenced from a line in the film about how Stanwyk’s cancer is destroying him bit by bit), plus other songs by Dan Hartman, The Fixx, and Kim Wilde. One of Faltermeyer’s pieces for a dream sequence not used in the film would end up getting used as the basis for the “Top Gun Anthem” for Top Gun a year later, at the suggestion of Billy Idol, for whom he provided keyboards for his “Whiplash Smile” tour, along with Idol’s lead guitarist, Steve Stevens. It would win the Grammy Award for Best Pop Instrumental Performance in 1987.

Done entirely in post-production, Chevy Chase’s narration ties the plot and motivation together while also tipping its hat to the old film noir detective stories of Hollywood’s yesteryear, even though the character is a reporter and not a private dick.

Trivia: there is a scene in which Fletch punches a framed picture of Stanwyk with then Los Angeles Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda claiming he hates Tommy Lasorda. This was intended to be a callback to another dream sequence, similar to one where Fletch imagines himself a superstar power forward for the Los Angeles Lakers, where he is a relief pitcher for the Dodgers that gets unceremoniously pulled from the game by Lasorda. However, it still makes for a funny moment despite the tie-in scene due to the unexpected and unexplained reaction from Fletch. The poster also reveals Fletch as a hockey player, revealing another fantasy that was removed from the final cut.

The adaptation from Andrew Bergman, who had scored a nice string of hit comedies with Blazing Saddles, The In-Laws and So Fine, is a loose construction of McDonald’s novel that he put together a draft for in less than a month’s time. He would find himself having to put in scenes based on what locations were available for a shoot. For instance, Ritchie had secured the use of an airplane hangar and asked Bergman to write a scene specifically to use an airplane and the hangar, resulting in the Gordon Liddy airplane inspector character and one of the funnier scenes in the film.

In the book, Alan Stanwyck is not directly tied in with the drug ring, instead merely revealed to be a bigamist who wants to fake his death. Initially, McDonald was very unhappy with Bergman’s take, but Michael Ritchie was able to show the author how things would end up working after inviting him to the set and eventually won him over. McDonald still maintains that the script isn’t how he would have done it, but acknowledges that the way he tried to do it wasn’t likely to have bee successful (if it were even made at all), so he’s content with what they were able to do given the Hollywood system. Chevy Chase claims that although Bergman’s name is on the credits, he is the actual writer of Fletch due to improvising all of the film’s best lines. Phil Alden Robinson and Jerry Belson later did some uncredited work on the script when revisions were needed while Bergman had moved on for a spell on another project he was set to direct.

Fletch benefits from a solid cast of character actors filling out the smaller roles from Richard Libertini as Fletch’s boss at the Times, Joe Don Baker as the corrupt and bullying cop, M. Emmett Walsh as Stanwyk’s jaded doctor, George Wendt as the drug-dealing Fat Sam. Tim Matheson does deliver in one of the better roles in his career as the man who seems trustworthy until you find out better. Dana Wheeler-Nicholson isn’t as seasoned as the romantic interest, Gail Stanwyk, but she exudes a nice naive charm that lends well for the role as someone who would find Fletch exciting, and also someone Fletch would find alluring in a world full of takers and leeches. Geena Davis also delivers a funny and memorable turn as Fletch’s Girl Friday at the paper, Larry, who happens to be the only actor in the film other than Chase who seems to be playing her part as a comedy.

Fletch would prove to be a box office success, debuting at #2 at the box office (behind the juggernaut Rambo: First Blood Part II in its second week of release) and remaining in the top ten in the U.S. for six weeks. It would rack up nearly $60 million internationally off of a reported budget of only $8 million.

It’s a fun film nonetheless and a must-see for Chevy Chase fans, as his particular gift of deadpan smartassery is on full display throughout. Though it is a quintessentially 80s movie in vibe, it still plays well for modern audiences and manages to deliver laughs without much of the vulgarity that permeates so many films of its ill. It’s also one of those movies that make its fans laugh in equal amounts on the tenth viewing than the first, and possibly even more as you catch jokes you may have missed before.

Qwipster’s rating: A

MPAA Rated: PG for violence and language

Running Time: 98 min.

Cast: Chevy Chase, Tim Matheson, Joe Don Baker, Dana Wheeler-Nicholson

Director: Michael Ritchie

Screenplay: Andrew Bergman (based on the novel by Gregory McDonald)