Jaws (1975)

Nearly a year prior to its publication in February 1974, film producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown, in collaboration with Universal Pictures, acquired the rights for a screen adaptation of “Jaws,” a novel being written by news reporter Peter Benchley. Benchley had the idea for “Jaws” after reading about Frank Mundus, a fisherman who caught a two-ton shark, imagining Ahab’s quest for a great white. Benchley, a self-described “shark freak,” spent his childhood summers shark hunting off the island of Nantucket, removing the jaws from sharks he caught as souvenirs. The completed story concerned a man-eating shark terrorizing a Long Island resort town.

The pre-release buzz was rare for a first-time writer like Benchley, known more for being the son of author Nathaniel Benchley and the grandson of humorist Robert Benchley. The unpublished manuscript sparked a fierce bidding war with Columbia Pictures, costing Zanuck/Brown $175,000, 10% of the profits, plus $75,000 for three screenplay revisions. Bantam paid $575,000 for the softcover edition rights.

Due to the difficult production, Zanuck/Brown sought an experienced hand to direct. Alfred Hitchcock, John Sturges, and others who made thrillers were considered. 27-year-old director Steven Spielberg, busy working on The Sugarland Express for Zanuck/Brown and Universal, spotted the manuscript on Zanuck’s desk and read it over the course of a weekend. When he finished reading, he felt he had the vision necessary to make a truly terrifying but highly commercial movie from this premise. He let Zanuck and Brown know of his interest but they already had a director, Dick Richards, who had the same talent agent as Benchley, Mike Medavoy, and came as part of the deal.

Spielberg didn’t wait long before the job opened up. Benchley didn’t want Richards to direct his film because he referring to the shark as a whale. Zanuck and Brown gave Spielberg a shot, though, by that time, the young director had talked himself out of it. He had qualms about taking on a high-profile effort, uncertain that he could deliver with a shark and an ocean shoot, knowing it could break his career if it didn’t come off well. He also had problems with Benchley’s book, especially its needless subplots, only interesting when the shark hunt was underway. Zanuck and Brown wore “Jaws” t-shirts Spielberg created to shame him back to taking the job.

Although technically a newcomer, Spielberg had directed films for over a decade. He made home movies as a kid with whatever movie equipment he could. He made his first film, a Western, at the age of thirteen starring his friends. In college, he made low-budget short films with money donated by people who believed in his talent. His 35mm short called, “Amblin”, won a couple of notable festival prizes and the attention of Sid Sheinberg, president of MCA and Universal Pictures. At the age of 21, and without enrolling in any film school, Spielberg dropped out of college with a seven-year-contract with one of the biggest entertainment studios in the world.

At this time, Spielberg envisioned himself as a “moviemaker” and not a filmmaker. Critics loved The Sugarland Express but it struggled at the box office. Spielberg said he’d trade away those raves for a larger audience. He didn’t make movies to please critics but to draw audiences.

Spielberg agreed to direct if he could make the characters likable and jettison what didn’t work from the book. Because the $3 million The Sugarland Express didn’t do well, Zanuck and Brown curtailed the Jaws budget to $2.5 million. Benchley wrote his first draft, essentially a transcript of the book, with the producers, then the second after Spielberg came aboard. The only issue they argued about was Spielberg’s idea for an ending involving the shark eating an air tank and Brody blowing it up. Benchley felt it wasn’t believable but Spielberg felt after two hours in the film he envisioned people would cheer in their seats. Benchley conceded after seeing the film that Spielberg did pull it off.

Receiving Benchley’s final draft, Spielberg told Zanuck and Brown he’d quit. He couldn’t see a good movie coming out of it and wanted to do another film he was offered called Lucky Lady. Sid Sheinberg, his mentor and one of the most powerful people in Hollywood, insisted he stay on Jaws. The producers sat with him and talked it out, with Spielberg writing a draft of what he wanted from the story and its characters. After the draft outline, they shopped around for writers that could flesh out a script. When “Columbo” creators William Link and Richard Levinson passed, Benchley’s third draft was handed to the uncredited playwright and scuba diver Howard Sackler, who worked with Spielberg to fix some of the issues he had. They removed the adulterous relationship between Hooper and Ellen because it emasculated their intended hero. Also gone was a Mafia real estate subplot involving the mayor. Benchley grew so incensed at the changes that he sent an angry letter to David Brown, escalating tension between all parties.

In a Newsweek interview, Spielberg asserted that Benchley’s view of his book was not his view of the movie he wanted to make of his book. Spielberg hated Benchley’s flawed and unlikeable characters and rooted for the shark to eat them all. He didn’t like the Peyton Place-esque romance and the overbearing allusions to “Moby-Dick.” He felt Jaws would be a major hit if he could strip the book down to its barest essence. Everyone finds sharks terrifying especially if they threatened people they know and love.

Benchley fired back, proclaiming Spielberg’s understanding of people came from movies he grew up watching and not real life, resulting in cliched stereotypes. He claimed that Spielberg would go down as the greatest second unit director in America. Spielberg squashed the problems by mentioning that Newsweek took a two-hour conversation and judiciously selected the more provocative quotes for their article, which Benchley, the former journalist, could relate.

Thinking things were turning sour, Zanuck and Brown offered to sell the rights to Peter Gimbel, a shark documentarian who advised the production early on who expressed an interest in directing the film. He declined, leaving them little choice but to get Spielberg to fully commit to directing the film to completion. Spielberg also tried to divorce himself from the film on several occasions. Without an approved script or complete cast, Zanuck and Brown were growing impatient, especially with an oncoming Actors Guild strike.

Seeking actors in a hurry, Zanuck and Brown wanted Charlton Heston for Brody but he was pricey and Spielberg didn’t want a huge star that audiences couldn’t view as an ordinary person. Spielberg had Joe Bologna in mind but the producers weren’t as keen. He pursued Robert Duvall but he didn’t want a lead part and asked to play Quint instead. Spielberg didn’t think he could pull it off, which he regretted thinking later.

Roy Scheider, who saw Spielberg sitting alone at a party and asked what was on his mind. Spielberg unloaded his issues with Jaws and putting together a cast in a hurry. Scheider asked, “What about me? I’d love to do it.” Spielberg took some time coming around because he thought Scheider was too much of a tough guy but eventually was offered the part. For Ellen Brody, Richard Zanuck wanted his wife, actress Linda Harrison, but Spielberg already promised the part to Sid Sheinberg’s wife, Lorraine Gary. Some speculated that Spielberg cast the studio head’s wife to avoid getting fired, but he insists she was the perfect Ellen.

For Matt Hooper, Jeff Bridges, Timothy Bottoms, and Joel Grey got looks. Jon Voight emerged as a favorite, as did Universal’s suggestion of Jan-Michael Vincent before George Lucas recommended American Graffiti co-star Richard Dreyfuss. Dreyfuss wasn’t interested, busy promoting The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, plus disliking the script. Disparaged that Duddy Kravitz would tank and make it hard for him to find work (it turned out a success), Dreyfuss reconsidered, provided Spielberg made changes to his character.

For Quint, Spielberg wanted Lee Marvin, but he was on a fishing vacation searching for real fish and didn’t want to cut that short to spend his summer pretending to catch a fake fish. Sterling Hayden was Zanuck/Brown’s top choice but he had tax entanglements in the U.S. Robert Shaw, hot off of Zanuck/Brown’s The Sting, signed on for the opposite reason. Shaw left England to avoid taxes, plus the $100,000 offered. Ironically, delays expanded his stay from six weeks to seventeen, causing him to pay taxes in the United States instead. Unlike veteran seaman Quint, Shaw spent every day on the ocean seasick. To nail down a New England accent and fisherman’s jargon, Shaw listened to a tape recording of a local landscape designer named Craig Kilsbury, who spent most of his life as a fisherman in the area (Kilsbury plays the ill-fated character named Ben Gardner in the film).

Not satisfied with Sackler’s dialogue, Spielberg asked his old friend, comedy writer Carl Gottlieb, who plays newspaper editor Harry Meadows, to give help polish the script with comic relief and additional character touches. Gottlieb roomed with Spielberg while at Martha’s Vineyard, inviting the actors for brainstorming sessions, making revisions for the next day’s shoot. Spielberg’s friend John Milius rewrote Sackler’s monologue on the sinking of the USS Indianapolis, which was put into the story to explain Quint’s abhorrence for sharks. Robert Shaw, a novelist himself who reconceived and condensed Milius’s eight-page speech to fit Quint. The actors also improvised some memorable lines, such as Scheider throwing in, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat.”

In the finished script, Amity, a New York island resort community, is about to enjoy its most popular season of the year, in the sun and fun of the 4th of July week. A teenage girl washes up on the beach, the victim of a shark attack. Amity police chief Martin Brody closes the beach but rescinds due to pressure from Amity’s mayor, closed beached would cost the tourism-dependent community dearly. Meanwhile, the attacks continue and try as they might to keep a lid on things, they are soon forced with a decision to close the beach or catch the shark themselves. Enlisting the help of a wealthy oceanographer (Dreyfuss) an eccentric shark hunter (Shaw), Brody tries to lure the shark near enough to kill.

The studio wanted him to shoot on a studio lot but Spielberg insisted that it needed to be out in the Atlantic ocean or the audience would not buy the story. As Spielberg traveled to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef to work with expert divers Ron and Valerie Taylor to capture underwater footage of great white sharks to use for the movie, production designer Joe Alves scouted locations in the northern Atlantic. Benchley modeled Amity after the Long Island town of Southampton, but shooting there or anyplace nearby would be difficult. Alves recommended Edgartown in Martha’s Vineyard because it afforded more privacy and contained every location they needed within five miles from their hotel.

Special effects gurus determined the action scenes were impossible with a real shark. Filming a great white underwater was dangerous enough, but surface and above-water elements were too difficult for even seasoned shark handlers. A mechanical shark that looked and moved like a real shark needed to be constructed. They interviewed many people who worked for Disney but none had any good answers. Spielberg hired retired Disney special effects head, Robert Mattey, designer of the squid in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Mattey crafted three mechanized polyurethane sharks that performed different tasks that cumulatively cost a half-million dollars.

The mechanical shark’s appearance came from a scarred-up 25-foot shark that Spielberg filmed in Australia. Spielberg called the shark “Bruce” after his lawyer, Bruce Ramer, and that name carried to the mechanized version. Saltwater corrosion prevented the shark from working often. To avoid further delays, Spielberg postponed showing the shark until late in the film, similar to 1951’s The Thing, which worked in the story’s favor. Audiences remained on edge, never knowing where and when the shark would strike.

Spielberg envisioned a tale of high adventure, a la Captains Courageous. He felt cinema should be an experience that you can’t get from watching TV at home. He wanted audiences to feel connected throughout. This would be a horror film in structure, but with a sociological portrait of a town mortified, making decisions between life and their livelihood. Spielberg felt humor should break the tension to keep audiences’ guards down for the next terrifying moment. He didn’t want a gorefest; implied violence is more effective in the minds of audiences that envision the worst.

Alves bought two boats, dubbed Orca and Orca II (meant to sink), repainting and redecorating them for the film. A tugboat with a generator accompanied the Orca to power the barges holding the lighting equipment and cameras, plus a mechanical shark that took thirteen technicians to operate. One day’s shooting, roughly $25,000, was the cost when the Orca sank (not the one intended) after springing a leak that caused the crew to quickly jump out before it would be covered by about 25 feet of water.

Bad weather and choppy seas pushed the shoot into late September, costing the production another $2 million. Each scene required lengthy preparation, necessitating consistent weather to match from shot to shot. While only the film’s final third is set on the water, two-thirds of the shoot was spent there. The actors found the water sequences exhausting to perform and mind-numbingly dull when waiting. Shaw groveled the most about the delays, especially when the length of the shoot cost him his next movie, a remake of Brief Encounter. Dreyfuss told David Brown that Jaws was the worst-produced film he’d ever been in.

Footage captured of a real great white saved Matt Hooper. The shark became entangled in the cables above the cage before they had Dreyfuss’ double inside it. The footage was so fantastic, Spielberg wanted it for the film, but the cage was empty. To get around this, they had Hooper drop his prod and leave the cage to retrieve it. Thus, Hooper remained alive despite dying in the screenplay.

Verna Fields worked with Spielberg to edit loads of footage to a tightly paced film. A workprint without underwater scenes or music fell flat and worried Universal. After considering Jerry Goldsmith scoring duties went to Sugarland Express‘s John Williams. Spielberg initially though the four-note score was a prank; Williams insisted he was serious and it would work. Once they matched the images to John’s music, Spielberg became convinced. That score is integral to the film’s suspense, keeping viewers on edge, mounting the tension to a fever pitch. Both Fields and Williams would earn Oscars for their contribution, as did the sound mixing team.

Once they screened a rough cut with the music intact, they knew they had a winner. Robert Shaw asked to exchange part of his salary for a profit percentage. Dreyfuss remarked that if he knew Jaws would be this good, he’d have had a better time making it. Preview screenings achieved audience ratings of 95% of ‘superb.’ Audio recordings revealed audiences laughing and shrieking at all of the appropriate times. Word of mouth had people lined up for four hours for further previews.

Very little needed to change from what Spielberg deliver, save for a bit of trimming of a gruesome scene involving a decapitated leg was done to avoid an R rating. They would market Jaws as the next big cinematic event that everyone needed to see, splashing $2.5 million into ads across the country, including the iconic advertisement of a massive shark coming up from the depths of the ocean to devour an attractive woman swimming above, a variation of the one used on the cover of Benchley’s book. Shark-mania swept the nation.

Jaws smashed box-office records, becoming the highest-grossing film to date. No other film in history took in over $100 million in the US, but Jaws racked up $260 million domestically. It also added another $200 million internationally, another record. It also received an Oscar nomination for Best Picture. Although his profit percentage was small (2.5%), Spielberg became a multi-millionaire.

Jaws turned Spielberg from an up-and-comer to an established major filmmaker. In theory, Jaws is b-movie fare, with little more to it than a shark terrorizing a resort community. Perhaps at the hands of an average director, this would have been junk cinema, only of appeal to schlock-lovers looking for a cheap thrill. Under Spielberg’s direction, this is anything but. Jaws is a surprisingly intelligent, powerful, riveting, and scary film that stays with you for a lifetime — a masterpiece of terror, with raw suspense that many filmmakers try but fail to recreate even to this day.

Jaws is one of the most brilliantly directed suspense vehicles since Hitchcock’s heyday. Just as Psycho made people afraid to go in the shower, Jaws did the same for the ocean. It forever planted in the mind that there are unseen dangers lurking below the water’s surface that can ravage a human being in seconds, in the most gruesome way imaginable. Spielberg uses a variety of tricks, many from Hitchcock, and some found in his smash debut, Duel, Spielberg’s television movie that honed his skills in how to create tension without words, letting the sounds of the score, the editing of the shots, and reactions of the actors drive the emotional turmoil and terror.

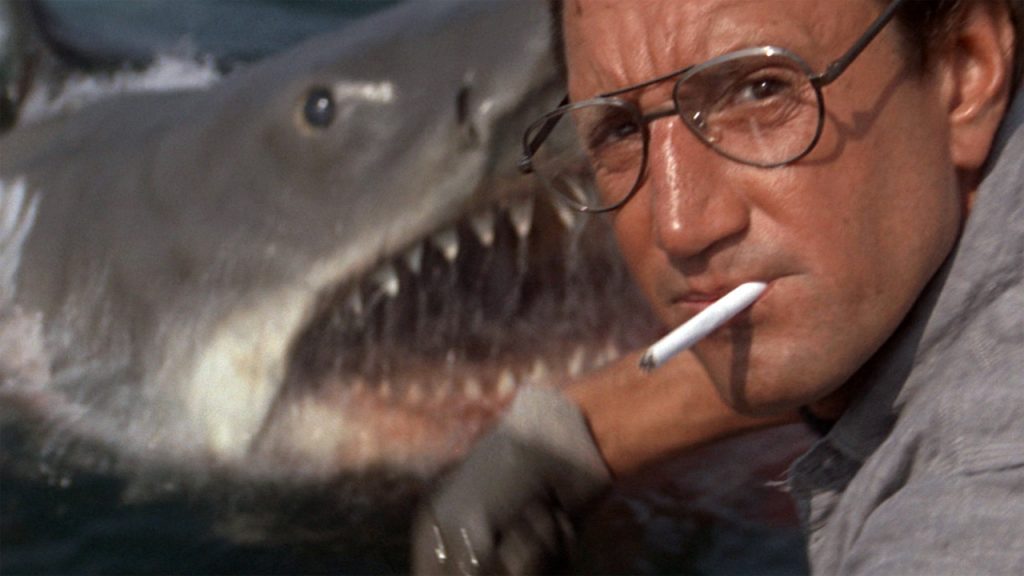

While Spielberg and composer John Williams are credited most for Jaws‘s success, the acting is equally important. Scheider is fantastic as Brody – confused, fearful, and determined as he should be in his situation. Richard Dreyfuss brings in energy and intelligence, a perfect foil for Robert Shaw’s more laid back and gut-driven approach to sailing the seas. All three play off of each other in fascinating ways, but Shaw often steals every scene with his perfect portrayal of a madman at sea, like Ahab chasing Moby Dick.

With excellent character development, a pitch-perfect delivery of mounting intrigue, and a climactic showdown that has audiences on edge throughout, Jaws is one of the greatest thrillers ever created — a blueprint for all movies achieving visceral suspense. Absolute must-see entertainment for fans of Spielberg, and everyone looking for a suspenseful good time.

Qwipster’s rating: A+

MPAA Rated: PG for violence, language, brief nudity, and a scene of drug use

Running Time: 124 min.

Cast: Roy Scheider, Robert Shaw, Richard Dreyfuss, Lorraine Gray, Murray Hamilton

Director: Steven Spielberg

Screenplay: Peter Benchley, Carl Gottlieb