They Live (1988)

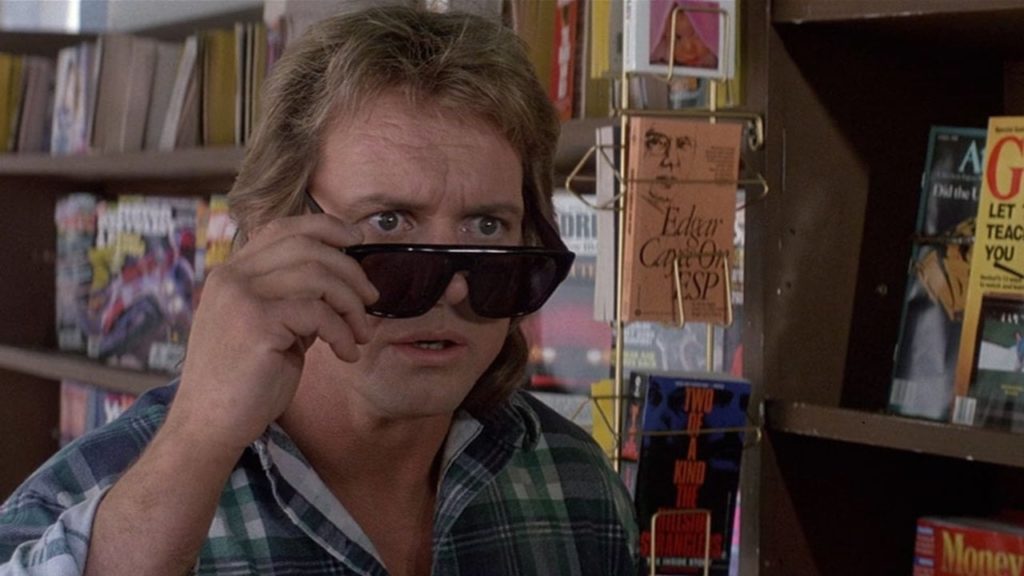

They Live is a laid-back sci-fi actioner starring ex-pro wrestler “Rowdy” Roddy Piper as John Nada (he’s not called any name in the movie), a drifter who lands a temp job at a construction site. Strange doings in the church across the street from the shantytown he resides in cause him to investigate. After the place is raided, he discovers what looks like ordinary sunglasses have specially engineered lenses to be able to see the world for what it really is.

He soon discovers that America is run by aliens who’ve become the one-percenters, brainwashing humans into submission through subliminal messages. Nada starts fighting back but makes himself a target of extermination. With no one believing him, it’s up to one man to try to take down a sinister and oppressive system singlehandedly.

After Big Trouble in Little China, John Carpenter took time off from filmmaking. What he saw on TV and in daily life sparked a rude awakening. Carpenter couldn’t believe, after all the social upheaval the country in the 1960s and 1970s, that America could support Ronald Reagan, embracing corporatism, commercialism, consumerism, materialism, and greed. Americans actually wanted the rich to be richer, brainwashed into thinking that the wealthy need more money so that the riches they spend would trickle down to the poorest among us.

While times were good for people at the top, the middle class faltered, many falling beneath the poverty line. Unions were dissolved while power shifted to favor corporations over workers. That Americans applauded this made Carpenter think many underwent brain death. The poor, the sick, the homeless were seen as dragging the system down rather than a byproduct of a system working only for the people at the top. And humans are willing to destroy the planet for future generations to make an extra buck today.

Everywhere we look someone is selling us something, conveying the message that if we aren’t buying, we aren’t living. Consumer culture has Americans in a stranglehold, weakening society by promoting greed as good and all other traits bad if they get in the way of financial success. The Reaganites were so clearly pro-profit and anti-everything decent that Carpenter couldn’t see the humanity in their actions. That the American people bought into this corporate power structure keeping them down was obviously the result of a skillful brainwashing effort.

Carpenter’s idea for They Live ignited after reading a comic book published by Eclipse Comics in 1985 called, “Alien Encounters #6”. Within its pages was a noirish eight-page tale called, “Nada”, (the Spanish word for ‘nothing’) written by Ray Faraday Nelson and illustrated by Bill Wray. “Nada” adapted Nelson’s short story, “Eight O’Clock in the Morning” published in November 1963 in “The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.” In the story, a man named George Nada is accidentally awakened by a stage hypnotist and finds that many people in society are actually lizard-like creatures with multiple eyes called “Fascinators.” They’ve put all humans under hypnosis to make them think they are also human while putting up posters around town with subliminal messages like, “Work 8 hours, play 8 hours, sleep 8 hours” and “Marry and reproduce.” Although Nada disconnects his TV, he can hear the televisions of his neighbors voicing things like, “Obey the government,” “We are the government”, and “We are your friends.”

The story resonated with Carpenter these feelings he held that he could see the ills of American society so clearly, yet he felt alone. What was obvious to him seemed invisible to everyone else – that the Reagan administration was a den of thieves and everyone was being hoodwinked into giving more money and power to the ultra-rich. These forces had shaped American society into conformity, and Carpenter wanted to awaken everyone from their current hypnotic state.

Carpenter secured the comic book rights and Nelson’s story. He updated them with a modern twist – the “Reagan revolution” was orchestrated by elitist aliens living among us, exploiting Earth like a third-world planet so they could live like royalty among us. They’re bombarding humans with messages within our media to keep us distracted while they steal our society out from under our feet, enslaving the poor and draining wealth from the middle class, living by the new Golden Rule: “Whoever has the gold makes the rules.”

His chosen title of “They Live” isn’t just about alien existence. Nada enters the church and sees graffiti on the wall reading, “They live, we sleep”. These insidious aliens are the ones who are living life the way it should be while the rest of humankind are either accomplices or living in a perpetual hypnotic fog.

Carpenter felt going mainstream in Hollywood hadn’t served him well, either commercially or creatively. He sold the rights to Halloween IV: The Return of Michael Myers in 1988. He wanted a return to the low-budget filmmaking of his early days when he had full creative control. Carpenter signed a four-picture deal with Shep Gordon and Andrew Blay’s Alive Films, granting him the artistic freedom to do one film a year costing $3-4 million for four years.

The films included Prince of Darkness, They Live, the time-travel actioner Victory Out of Time (written by Carpenter’s then-girlfriend and future wife script supervisor Sandy King), and a fourth to be named later. Alive sold the domestic distribution rights to Universal Pictures and international to Carolco. MCA, Universal’s parent company, was reticent about Carpenter’s anti-corporate message, thinking he had set his sights on them. Universal chair Tom Pollock suggested Carpenter expand the alien motivation beyond money, perhaps wanting humans for food. Carpenter had final cut, so he kept it as is. An executive at Universal asked Carpenter why it was a threat to humanity to sell out for money because we all do it every day. Carpenter used that line in the film.

Carpenter was reminded of a book by Joe McGinness called “Fatal Vision” chronicling how Jeffrey McDonald killed his family without remorse or a sense of morality. He had no concept of right and wrong. He felt that money was causing people to push away morality out of self-interest, perhaps even self-reservation, allowing others to suffer so that they could prosper, without a pang of guilt at all at what the nation was becoming. In our current society, the true lives of the poor are invisible to the rich. The rich don’t want to see the poor because seeing them means having to do something about them. They’d rather live without a care in the world. Carpenter felt that the true nature of the rich was equally invisible to the poor.

Carpenter’s concept for the film, in which the aliens, dubbed ghouls, weren’t seen in their natural state unless through special sunglasses. He didn’t want to do hypnosis because it explained things too quickly and it was important for Nada to get others to experience with him. Sunglasses offered a visual to explain without needing words. A frequency wave connection to a TV station provides a shortcut to explain the technology behind the mass hypnosis. The vision of reality in black and white recalls The Wizard of Oz, where black and white represents the reality of Dorothy’s existence, while color is her fantasy. In this way, Carpenter also comments on Ted Turner’s colorizing classic films purely for money.

Carpenter worked with cinematographer Gary Kibbe because he trusted his expertise on cameras, promoting him for Prince of Darkness. He captured the sunglasses’ point-of-view vision in decolorized black and white to see the subliminal messages all around. Messages include, “watch TV”. “marry and reproduce”, “obey”, “submit”, “stay asleep”, “no independent thought”, “conform”, “consume”, “do not question authority”, “honor apathy”, and “doubt humanity”. Dollar bills display the message: “This is your God.”

Carpenter’s friend and frequent collaborator Jim Danforth handled visual effects, doing some stop-motion animation and matte paintings, including POV shots from color to black-and-white. They intended to add electronic interference to simulate the painful process of prolonged use of sunglasses but it was too costly so they simulated headaches. The idea was that it’s painful to see the truth – the pain we avoid by living in ignorance.

As he set to write, Carpenter knew he needed a hero audiences would enjoy. Many of Carpenter’s heroes share qualities of a certain close friend he had growing up. Kurt Russell fit this mold but Carpenter couldn’t afford him or any of the many alternates he considered. A wrestling fan since childhood, Carpenter cast Piper after attending his retirement match in the Silverdome at Wrestlemania III and seeing many of those qualities within him. He liked Piper’s tough, scarred but kind face. He looked like someone who lived a life of hard work rather than glamor. He oozed charisma yet remained down to earth. He invited him to dinner to make him the movie offer.

Although he didn’t know who John Carpenter was at the time, Piper couldn’t say no to a starring role in a major motion picture. He didn’t even ask what it was about. He just wanted to increase his worth outside of the World Wrestling Federation. Vince McMahon didn’t want Piper to make movies with someone else, offering him a movie within four weeks for the same fee. Piper proceeded with They Live, splitting from the WWF into uncharted waters.

Because his lead was inexperienced, Carpenter tailored Nada around Piper’s persona – his father issues, leaving home as a teenager, homelessness, working odd jobs. He refused to take his wedding band off, just as he refused when wrestling. While Carpenter was writing the script, Piper handed over several sheets of notebook paper containing phrases he used during wrestling interviews like, “Life’s a bitch and she’s back in heat,” and “I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass, and I’m all out of bubblegum.”The 1996 video game “Duke Nukem 3D” also paraphrased that line, popularizing it for a generation of gamers.

Carpenter cast Keith David after enjoying his work in his 1982 film The Thing. David came to the Prince of Darkness premiere and Carpenter observed him as someone who could stand his own against Piper and mentor his inexperienced actor. David seemed interested, so he wrote the character of Frank Armitage for him. Carpenter used the name “Frank Armitage” for his screenplay credit. Carpenter initially claimed Armitage was a real-life first-time writer that was like a brother who thought like he did that he was giving a break in films. He didn’t want credit because many concepts came from other sources, especially Ray Nelson, plus input from Roddy Piper and Sandy King. The name comes from an H.P. Lovecraft short story called “The Dunwich Horror”. Carpenter is an admirer of Lovecraft, especially in his hidden worlds that live under the surface.

As Piper was a popular wrestler, he would handle the stunts (except for a fall out of a window). Carpenter wanted his fans to see him do his thing. He developed a wrestling match between Nada and Frank. Frank doesn’t want to put on the sunglasses because finding out the truth meant having to act. He’d rather live in willful ignorance to provide money for his family. Nada’s task is to force Frank into seeing that they are all being used and to break out of his hypnotic state. Frank fights tooth and nail to keep living in the false reality because his family needs the money. Many people turn a blind eye to what’s going on in the world they don’t want to see.

Their fight was written in the script as, “The Fight Begins” followed by several pages of “The Fight Continues,” and then “The Fight Concludes”. Stunt coordinator Jeff Imada (who plays most of the ghouls) choreographed Piper and David with Carpenter’s only instruction being to include three wrestling moves: a clothesline, suplex, and body slam. Carpenter, who dreamed of making Westerns, emulated the lengthy fight between John Wayne and Victor McLaglen in John Ford’s The Quiet Man. He wanted this fight to last longer.

They rehearsed six weeks in Carpenter’s office backyard on the choreography, including actual physical contact. They added dialogue and character touches to show their progression from frenemies to allies. The scene took four days to shoot in a padded alleyway. The on-screen fight takes up over five minutes of screen time. Imada says Carpenter cut over a minute out of the full fight. The absurdity of the fight is meant symbolize the difficulty in changing someone’s worldview; it’s easier to con someone than to convince them they’ve been conned.

They Live is wish-fulfillment backlash towards the “Me Generation” and their single-minded quest for wealth and power. It’s no coincidence that all of the aliens are affluent whites. Humans that abet the enemy gain privileges by betraying their own kind. One human Nada tries to wake says that if she puts on his glasses, she’ll tell him she sees whatever he wants her to see, indicating that, like so many living under oppression, she’ll do whatever is necessary to survive by placating those who have the power.

Carpenter worked with Prince of Darkness makeup artist Frank Carissosa for the Sandy King-conceived ghouls. They’re essentially humans whose corruption has drained them of humanity – barely retaining the last shred of the human form before decomposing into nothingness. Their continued existence requires that no one knows or cares that the world is controlled by those at the top, resolved to obey, and keep food on the table.

John Carpenter and Alan Howarth collaborated on the memorable music. Carpenter wanted to evoke “The Grapes of Wrath” so opted for a downtrodding bluesy vibe. The score features blues guitar, harmonica, and saxophone. Alas, due to a dispute over money issues, it was the last Carpenter collaboration with Howarth.

Originally slated for an October 7 release, They Live came out on November 4, 1988, perhaps too close to the November 8 election day for its warnings to sink in. George H.W. Bush won the presidency, continuing the Reagan legacy. It was a hit in that it made $13 million off of a budget of $4 million, debuting at #1 but falling mostly out of theaters by Thanksgiving. Carpenter said the public’s ignoring of They Live was like the refusal to put on the glasses. They would rather “sleep” and “obey”.

Critics were mixed. Some expected Carpenter to make better movies with final cut while others railed against the gratuitous violence, spoofed in the movie with Siskel-and-Ebert-like TV critics calling out Carpenter by name. Other critics complained about bad acting (singling out Piper), cheesy dialogue, and lackluster effects. Some praised its b-movie charm and enjoyable goofiness. Today it’s considered an overlooked cult-classic.

While much better than one would expect given the inexperienced star and small budget, it’s still a bit frustrating that it doesn’t live up to its own promise and premise, and while still recommended for campy fun with something to think about, what we’re left with is a great idea for a movie that is more entertaining than enlightening. Conceptually, They Live is brilliant, and its concepts will likely be enough for many to overlook its inherent issues as a narrative.

With more time, Carpenter could have fleshed out that concept to make a real masterwork. With a larger budget and more development of the screenplay, Carpenter had the potential to make great sci-fi rather than just have great satirical ideas. These ideas explored by They Live lie mostly in the beginning, descending into a slow-moving low-budget actioner that, while maintaining entertainment, isn’t as compelling as the setup. However, those ideas inspired future filmmakers to try new takes on that concept, with 1999’s The Matrix perhaps the most successful example.

Carpenter was allowed one outside big-budget film during the Alive Films contract period. Carpenter passed on several big-budget projects, opting to make Escape from L.A. for DEG. Alas, it all went wrong. DEG went bankrupt, while his contract with Alive Films was aborted after Carpenter had disputes with Universal. Carpenter sued Gordon and Blay for $3.6 million in 1990 and they countersued for $7.5 million, also for breach of contract, contending that Carpenter wouldn’t deliver the third film, Victory Out of Time, on schedule due to the writer’s strike that left the screenplay on hold. His intended sequel called They Live II: Hypnowar never got made.

Carpenter never woke America against Reagan’s policies, which never ended. Unrestrained capitalism brought the Great Recession, the middle class bearing the bring, while no punishment for the ghouls who created it. Carpenter says that Donald Trump, who blossomed in the Reagan era, is the epitome of a ghoul, hiding his efforts to feast under a coiffed mane and tailored suit. He is saddened to realize, despite his film being around for over thirty years, that people still buying into the messages, except they don’t need to be subliminal anymore. It’s the working poor that supports the ghoul agenda most of all.

- Since 2008, Universal Pictures and Strike Entertainment, who produced the prequel to The Thing, tried to remake They Live. D.B. Weiss was assigned to the first script, In 2011, Matt Reeves came in to write and direct, changing the name to Resistance, intending more a psychological horror adaptation of the Ray Nelson story than a remake of the film. It has remained in development hell ever since.

- A sequence in the 2001 “South Park” episode called “Cripple Fight” spoofed the fight between Nada and Frank.

- The 2013 game “Saints Row IV” pays great homage, including featuring Keith David as a character in a nightmare brawl simulation against Roddy Piper in his WWF garb. Both David and Piper provide their voices.

- Green Day (“Back in the USA”), Armand van Helden (“Into Your Eyes”), and Anti-Flag (“The Disease”) made music videos that recreate images from the film.

- In 2017, Carpenter strongly pushed back on white supremacist claims the film is about Jews controlling the world.

Qwipster’s rating: B

MPAA Rated: R for violence including a brutal fight, language, and brief sexuality/nudity.

Running Time: 93 min.

Cast: Roddy Piper, Keith David, Meg Foster, George Flower, Peter Jason

Director: John Carpenter

Screenplay: John Carpenter (as Frank Armitage)